Not sure if Pratt is canceling class for tomorrow, so I am just going to do it myself.

If Pratt does cancel it they will assign a makeup date.

If it doesn't get officially canceled, we will figure out a makeup session when we next meet.

Don't forget March 6th: Timothy Briner visiting artist lecture. Invite people.

Max

Friday, February 26, 2010

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Class 3 recap.

Last class we looked at some photographers working around mid 1850s through the later part of the 20th century who were either doing war photography or some sort of landscape themed excursion work (for both personal and sponsored projects) I tie these together because while obviously being very different, there is a similar sense of photographic uncharted history brought to the public by them. In the first class we talked about how photography was able to take the viewer to a place that before was only a description. This wasn't just relevant to travel photography; think of the devastating effects that showing images of war had on people who never experienced it.

Roger Fenton

1819–69, English pioneer photographer. Originally a barrister, Fenton worked from the early 1850s until 1862 as a fashionable architectural, still-life, portrait, and landscape photographer. Aesthetically sensitive and technically adept, he was the most acclaimed and influential photographer in England during this period and did much to establish photography as both an art and a profession. Fenton had a strong interest in Orientalist subjects and he also made (1852) a series of photographs of Moscow and Kiev.

Sponsored by the royal family, he was commissioned in 1855 to document the Crimean War.

Working under appalling conditions, he made 360 photographs emphasizing the romantic aspects of an unpopular war. His few combat pictures are among the earliest photographs of battle. While these photographs present a substantial documentary record of the participants and the landscape of the war, there are no actual combat scenes, nor are there any scenes of the devastating effects of war.

Fenton purchased a former wine merchant's van and converted it to a mobile darkroom. He hired an assistant, and traveled the English countryside testing the suitability of the van. In February 1855 Fenton set sail for the Crimea aboard the Hecla, traveling under royal patronage and with the assistance of the British government.

But Fenton shied away from views that would have portrayed the war in a negative (or realistic) light for several reasons, among them, the limitations of photographic techniques available at the time (Fenton was actually using state-of-the-art processes, but lengthy exposure time prohibited scenes of action); inhospitable environmental conditions (extreme heat during the spring and summer months Fenton was in the Crimea); and political and commercial concerns (he had the support of the Royal family and the British government, and the financial backing of a publisher who hoped to issue sets of photos for sale).

"...in coming to a ravine called the valley of death, the sight passed all imagination:

round shot and shell lay like a stream at the bottom of the hollow all the way down, you could not walk without treading upon them..."

--Roger Fenton

On first look, this image looks like a normal landscape photograph, it is only once you look close and realize the sheer amount of cannon balls that lay on what seems like a never ending road do you truly realize how this photo can say so much about a war without showing you any actual action from it.

More on Fenton and the Crimean War

1861-65: Mathew Brady and staff (mostly staff) covers the American Civil War, exposing 7000 negatives

Brady thought it would be a good idea to photograph the entire war and was sure the American government would later purchase his photos and he would at least make back the $100,000 or so he had invested in the project.

While Brady hired roughly 20 photographers such as Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan to work under him, part of the deal was that they could not attain any personal credit for their work and everything shot by them was to be signed as Mathew Brady.

This of course did not suit some of the photographers and they went on to branch off and do their own work without the supervision of Brady, who really didn't even shoot the actual war that much but was more in charge of the supervisions and organization of the project and more of the portraits associated with the war.

The war had come to an end in 1865 and by 1873 Brady was far in debt, having to sell off his New York studio. He did, however, manage to finally get the gvt. to buy his project for a whopping $2840...for those of you with minimal math skills that's a loss of $97,160.

Here are a couple video essays about Brady photos from a historian at the University of Iowa.

Many of the photographers hired by Brady, such as Alexander Gardner were unhappy with not being able to take credit for their work and went on to quit. Gardner had opened up his own studio in D.C. and kept working on the Civil War project without the assistance of Brady and actually had the Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, a two-volume collection of 100 original prints, published in 1866.

amongst the genuine pictures of the war there appear to be a few which are contrived, further proof that whilst people may think the camera cannot lie, the person behind it can! For example, when Gardner arrived at the decisive scene of the war at Gettysburg two days after it had been fought, he set about photographing "Home of a rebel sharpshooter." However, before taking the picture he had dragged the body of a Conferedate some thirty metres to where he lies in the picture, turning the head towards the camera.

So, does the camera ever lie? Well, as digital photography grows apace, almost anything is achieveable! But what of the past? Like any artist, a photographer may want to portray some emotion, evoke a reaction, put out a thought of his own. The lens sees what it sees, but what appears is inevitably subjective.

When Daguerre exclaimed that photography was "an absolute truth, infinitely more accurate than any painting by the human hand," he probably wasn't thinking of how photographers would be using this public perception to not only push their agenda but just as simply fool the public. While the war photographers of the time were not necessarily trying to do either, the facts are simple: photographing action in the 1860s was really hard, photos were staged, war scenes were tampered with for the sake of better photos.

Is this acceptable? Does the photographer have a right to do such a thing? Does it matter if the photograph is an absolute truth if it serves a greater purpose like changing people's perception of the world for a greater truth or is that too close to propaganda?

What about this recent controversy?

Timothy O'Sullivan - by 1870, ex brady photographers such as o'sullivan and william jackson headed west on government funded exhibitions to document landscapes. O'Sullivan approached western landscape with the documentarian's respect for the integrity of visible evidence and the camera artist's understanding of how to isolate and frame decisive forms and structures in nature.

A sense of mysterious silence and timelessness; these qualities may be even more arresting to the modern eye than they were to his contemporaries, who regarded his images as accurate records rather than evocative statements.

William Henry Jackson

His pictures helped convince the Congress of the United States to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Active throughout the Western United States from 1870 to the early 1900s, Jackson had a long and illustrious career working for government survey parties and producing views that were sold by the thousands as postcards to the general public.

Jackson carried plates as large as 50 by 61 cm (20 by 24 in) into remote and mountainous regions now part of Colorado, Wyoming, and other Western states. His landscape pictures are sharp and dramatic, and helped influence many of the 20th century landscape photographers such as Edward Weston and Ansel Adams as well as set a precedent for postcard production.

william henry jackson collection

Library of congress info about photographing civil war

Roger Fenton

1819–69, English pioneer photographer. Originally a barrister, Fenton worked from the early 1850s until 1862 as a fashionable architectural, still-life, portrait, and landscape photographer. Aesthetically sensitive and technically adept, he was the most acclaimed and influential photographer in England during this period and did much to establish photography as both an art and a profession. Fenton had a strong interest in Orientalist subjects and he also made (1852) a series of photographs of Moscow and Kiev.

Sponsored by the royal family, he was commissioned in 1855 to document the Crimean War.

Working under appalling conditions, he made 360 photographs emphasizing the romantic aspects of an unpopular war. His few combat pictures are among the earliest photographs of battle. While these photographs present a substantial documentary record of the participants and the landscape of the war, there are no actual combat scenes, nor are there any scenes of the devastating effects of war.

Fenton purchased a former wine merchant's van and converted it to a mobile darkroom. He hired an assistant, and traveled the English countryside testing the suitability of the van. In February 1855 Fenton set sail for the Crimea aboard the Hecla, traveling under royal patronage and with the assistance of the British government.

But Fenton shied away from views that would have portrayed the war in a negative (or realistic) light for several reasons, among them, the limitations of photographic techniques available at the time (Fenton was actually using state-of-the-art processes, but lengthy exposure time prohibited scenes of action); inhospitable environmental conditions (extreme heat during the spring and summer months Fenton was in the Crimea); and political and commercial concerns (he had the support of the Royal family and the British government, and the financial backing of a publisher who hoped to issue sets of photos for sale).

"...in coming to a ravine called the valley of death, the sight passed all imagination:

round shot and shell lay like a stream at the bottom of the hollow all the way down, you could not walk without treading upon them..."

--Roger Fenton

On first look, this image looks like a normal landscape photograph, it is only once you look close and realize the sheer amount of cannon balls that lay on what seems like a never ending road do you truly realize how this photo can say so much about a war without showing you any actual action from it.

More on Fenton and the Crimean War

1861-65: Mathew Brady and staff (mostly staff) covers the American Civil War, exposing 7000 negatives

Brady thought it would be a good idea to photograph the entire war and was sure the American government would later purchase his photos and he would at least make back the $100,000 or so he had invested in the project.

While Brady hired roughly 20 photographers such as Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan to work under him, part of the deal was that they could not attain any personal credit for their work and everything shot by them was to be signed as Mathew Brady.

This of course did not suit some of the photographers and they went on to branch off and do their own work without the supervision of Brady, who really didn't even shoot the actual war that much but was more in charge of the supervisions and organization of the project and more of the portraits associated with the war.

The war had come to an end in 1865 and by 1873 Brady was far in debt, having to sell off his New York studio. He did, however, manage to finally get the gvt. to buy his project for a whopping $2840...for those of you with minimal math skills that's a loss of $97,160.

Here are a couple video essays about Brady photos from a historian at the University of Iowa.

Many of the photographers hired by Brady, such as Alexander Gardner were unhappy with not being able to take credit for their work and went on to quit. Gardner had opened up his own studio in D.C. and kept working on the Civil War project without the assistance of Brady and actually had the Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, a two-volume collection of 100 original prints, published in 1866.

amongst the genuine pictures of the war there appear to be a few which are contrived, further proof that whilst people may think the camera cannot lie, the person behind it can! For example, when Gardner arrived at the decisive scene of the war at Gettysburg two days after it had been fought, he set about photographing "Home of a rebel sharpshooter." However, before taking the picture he had dragged the body of a Conferedate some thirty metres to where he lies in the picture, turning the head towards the camera.

So, does the camera ever lie? Well, as digital photography grows apace, almost anything is achieveable! But what of the past? Like any artist, a photographer may want to portray some emotion, evoke a reaction, put out a thought of his own. The lens sees what it sees, but what appears is inevitably subjective.

When Daguerre exclaimed that photography was "an absolute truth, infinitely more accurate than any painting by the human hand," he probably wasn't thinking of how photographers would be using this public perception to not only push their agenda but just as simply fool the public. While the war photographers of the time were not necessarily trying to do either, the facts are simple: photographing action in the 1860s was really hard, photos were staged, war scenes were tampered with for the sake of better photos.

Is this acceptable? Does the photographer have a right to do such a thing? Does it matter if the photograph is an absolute truth if it serves a greater purpose like changing people's perception of the world for a greater truth or is that too close to propaganda?

What about this recent controversy?

Timothy O'Sullivan - by 1870, ex brady photographers such as o'sullivan and william jackson headed west on government funded exhibitions to document landscapes. O'Sullivan approached western landscape with the documentarian's respect for the integrity of visible evidence and the camera artist's understanding of how to isolate and frame decisive forms and structures in nature.

A sense of mysterious silence and timelessness; these qualities may be even more arresting to the modern eye than they were to his contemporaries, who regarded his images as accurate records rather than evocative statements.

William Henry Jackson

His pictures helped convince the Congress of the United States to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Active throughout the Western United States from 1870 to the early 1900s, Jackson had a long and illustrious career working for government survey parties and producing views that were sold by the thousands as postcards to the general public.

Jackson carried plates as large as 50 by 61 cm (20 by 24 in) into remote and mountainous regions now part of Colorado, Wyoming, and other Western states. His landscape pictures are sharp and dramatic, and helped influence many of the 20th century landscape photographers such as Edward Weston and Ansel Adams as well as set a precedent for postcard production.

william henry jackson collection

Library of congress info about photographing civil war

Martin Parr book signing

Clic Gallery is pleased to present the legendary photographer MARTIN PARR signing his most recent monograph LUXURY, published by Chris Boot. Featuring an introduction by fashion designer Sir Paul Smith, LUXURY is Parr's series of satirical color photographs documenting the gaudy extremes of the boom years. Garish shots of diamond jewelry, bored waiters, shopping bags, and champagne-fueled parties in Dubai, Moscow and Beijing are vintage Parr, showcasing his dry humor and fondness for kitsch.

Born in the UK in 1952, MARTIN PARR is the author of over 30 books of photography, and his work is in the permanent collections of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Tate Modern in London. He is a member of Magnum Photos and has been the subject of retrospectives at the Barbican Art Gallery and the New Media Museum. During his appearance at Clic, Martin Parr will also sign copies of his other works, including MEXICO and PARRWORLD: OBJECTS AND POSTCARDS.

The LUXURY SPECIAL EDITION, of which only one hundred have been made, will also be available for sale at Clic Gallery. This collector's item features book pages gilt-edged in silver, calf leather binding and slipcase, and is sold with a signed Martin Parr print.

To pre-order a signed copy, please call 212-966-2766 or click here.

Clic Bookstore & Gallery

255 Centre Street, New York, NY 10013

Tue-Sun 12 pm - 7 pm

centre@clicgallery.com

212-966-2766

Monday, February 22, 2010

Shows we saw last class.

Jan Dibbets: New Horizons

Gladstone Gallery

Michael Kenna: Venezia

Robert Mann Gallery

Robert Adams: Summer Nights, Walking

Mathew Marks Gallery

Friday, February 19, 2010

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Some contemporary artists working with older processes.

NewDags showcases some contemporary Daguereotype artists

Robert W. Schramm

Here is some work by my friend Galina Kurlat, who makes wet plates.

Joni Sternbach is another Brooklyn based photographer (who also happened to study with John Coffer) working with older / alternative process whose work has been getting a lot of attention recently.

She will be holding a 2 day wet plate workshop on March 13th and 14th through ICP at her Brooklyn studio.

Robert W. Schramm

Here is some work by my friend Galina Kurlat, who makes wet plates.

Joni Sternbach is another Brooklyn based photographer (who also happened to study with John Coffer) working with older / alternative process whose work has been getting a lot of attention recently.

She will be holding a 2 day wet plate workshop on March 13th and 14th through ICP at her Brooklyn studio.

cartes-de-visite

Cartes-de-visite were small visiting card portraits (usually measuring 4 1/2 x 2 1/2") introduced by a Parisian photographer, Andre Disdéri, who in late 1854 patented a way of taking a number of photographs on one plate (usually eight), thus greatly reducing production costs. (He was not actually the first to produce them; this honour belongs to an otherwise obscure photographer called Dodero, from Marseilles).

Different types of cameras were devised. Some had a mechanism which rotated the photographic plate, others had multiple lenses which could be uncovered singly or all together.

In England carte-de-visite portraits were taken of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. One firm paid a small fortune for exclusive rights to photograph the Royal Family, and this signaled the way for a boom in collecting pictures of the famous, or having one's own carte-de-visite made. It is said that the portraits of Queen Victoria and the Royal Family taken by John Mayall sold over one hundred thousand copies.

Other public figures were often persuaded to sit. Helmut Gernsheim, a writer on the history of photography, comments that they were called "sure cards" because one could be sure that each time a famous person consented to sit, a small fortune would go to the photographer! To print quickly, several negatives were taken at a sitting: the Photographic News for 24 September 1858 reported that no fewer than four dozen negatives were taken of Lord Olverston at one sitting!

During the 1860s the craze for these cards became immense. An article in the Photographic Journal, reports:

"The public are little aware of the sale of the cartes de visite of celebrated persons. As might be expected, the chief demand is for members of the Royal Fanily.... No greater tribute to the memory of His late Royal Highness the Prince Consort would have been paid than the fact that within one week of his decease no less than 70,000 of his cartes de visite were ordered...

Our great thoroughfares are filled with photographers; there are not less than thirty-five in Regent Street alone."

Sometimes the profits could be huge. A Frenchman by the name of Oliver Sarony, who was based in Yorkshire, was said to be earning more then ten thousand pounds a year - a fortune last century. Little wonder that there was speculation that Gladstone might introduce a tax on the trade!

By the way, pirating of someone else's work is not new; some firms copied the photograph of a famous person and made quite a healthy living!

The reasons for the success of these cards were

* their cheapness. The average price for a card was a shilling

* they were small, light and easy to collect, and many people began to place these in photographic albums

* collections of pictures, particularly of royalty, became highly treasured

Cartes-de-visite were Albumen prints, and it is on record that in Britain half a million eggs were being delivered yearly to one photographic studio alone!

The props used in cartes-de-visite seemed to follow certain fashions; starting off with balustrades and curtains, they moved to columns (sometimes resting on the carpet!) bridges and stiles, hammocks, palm-trees and bicycles. Sadly, quantity rather than quality was the order of the day, though there are some striking exceptions.

To some extent the carte-de-visite craze also put paid to photography in which detail was a distinctive feature; the work of Gustave Le Gray (we'll learn about him next class) and of the Bisson brothers, for example, could not be reproduced on these small cards, and thus their businesses began to fall off.

By 1860 the carte de visite craze had reached its climax. In his autobiography H. P. Robinson (also will learn about him next class) states that in 1859 his photographic business had been about to collapse, but that this innovation had saved it. By the end of 1860 he had not only paid off old debts and made additions to his premises, but had invested a considerable sum of money, two years later being able to sell his business and retire to live in London.

In May 1862, Marion & Co. announced that it had published a series of Cabinet views, 6.75 x 4.5 inches, photographed by George Washington Wilson, and the larger Cabinet photographs remained in vogue until the postcard was introduced at the turn of the century. Stereoscopic cards, whose popularity had temporarily declined, also began to experience a revival.

There are many examples of these photographs in the Royal Photographic Society's collection. Some on current display are accompanied by an advertisement by the London Stereoscopic Society, for twenty prints at one pound, "Detention 3 minutes."

text from rleggat

An original albumen contact print from a wet-plate negative. The portrait session was shot in Disderi's Paris studio. Unknown sitter.

While individual cartes de visite by him are not rare items, these uncut "proof" sheets are very difficult to find, and represent a fascinating glimpse into the world of the studio photographer in the mid-1800s.

Note there are four sets of two poses each. The images are not stereoscopic (like the ones we learned about last class and saw examples of at the No Man's Land exhibit at Rick Wester Fine Art ) they are simply 'Take 1 and Take 2'

Different types of cameras were devised. Some had a mechanism which rotated the photographic plate, others had multiple lenses which could be uncovered singly or all together.

In England carte-de-visite portraits were taken of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. One firm paid a small fortune for exclusive rights to photograph the Royal Family, and this signaled the way for a boom in collecting pictures of the famous, or having one's own carte-de-visite made. It is said that the portraits of Queen Victoria and the Royal Family taken by John Mayall sold over one hundred thousand copies.

Other public figures were often persuaded to sit. Helmut Gernsheim, a writer on the history of photography, comments that they were called "sure cards" because one could be sure that each time a famous person consented to sit, a small fortune would go to the photographer! To print quickly, several negatives were taken at a sitting: the Photographic News for 24 September 1858 reported that no fewer than four dozen negatives were taken of Lord Olverston at one sitting!

During the 1860s the craze for these cards became immense. An article in the Photographic Journal, reports:

"The public are little aware of the sale of the cartes de visite of celebrated persons. As might be expected, the chief demand is for members of the Royal Fanily.... No greater tribute to the memory of His late Royal Highness the Prince Consort would have been paid than the fact that within one week of his decease no less than 70,000 of his cartes de visite were ordered...

Our great thoroughfares are filled with photographers; there are not less than thirty-five in Regent Street alone."

Sometimes the profits could be huge. A Frenchman by the name of Oliver Sarony, who was based in Yorkshire, was said to be earning more then ten thousand pounds a year - a fortune last century. Little wonder that there was speculation that Gladstone might introduce a tax on the trade!

By the way, pirating of someone else's work is not new; some firms copied the photograph of a famous person and made quite a healthy living!

The reasons for the success of these cards were

* their cheapness. The average price for a card was a shilling

* they were small, light and easy to collect, and many people began to place these in photographic albums

* collections of pictures, particularly of royalty, became highly treasured

Cartes-de-visite were Albumen prints, and it is on record that in Britain half a million eggs were being delivered yearly to one photographic studio alone!

The props used in cartes-de-visite seemed to follow certain fashions; starting off with balustrades and curtains, they moved to columns (sometimes resting on the carpet!) bridges and stiles, hammocks, palm-trees and bicycles. Sadly, quantity rather than quality was the order of the day, though there are some striking exceptions.

To some extent the carte-de-visite craze also put paid to photography in which detail was a distinctive feature; the work of Gustave Le Gray (we'll learn about him next class) and of the Bisson brothers, for example, could not be reproduced on these small cards, and thus their businesses began to fall off.

By 1860 the carte de visite craze had reached its climax. In his autobiography H. P. Robinson (also will learn about him next class) states that in 1859 his photographic business had been about to collapse, but that this innovation had saved it. By the end of 1860 he had not only paid off old debts and made additions to his premises, but had invested a considerable sum of money, two years later being able to sell his business and retire to live in London.

In May 1862, Marion & Co. announced that it had published a series of Cabinet views, 6.75 x 4.5 inches, photographed by George Washington Wilson, and the larger Cabinet photographs remained in vogue until the postcard was introduced at the turn of the century. Stereoscopic cards, whose popularity had temporarily declined, also began to experience a revival.

There are many examples of these photographs in the Royal Photographic Society's collection. Some on current display are accompanied by an advertisement by the London Stereoscopic Society, for twenty prints at one pound, "Detention 3 minutes."

text from rleggat

An original albumen contact print from a wet-plate negative. The portrait session was shot in Disderi's Paris studio. Unknown sitter.

While individual cartes de visite by him are not rare items, these uncut "proof" sheets are very difficult to find, and represent a fascinating glimpse into the world of the studio photographer in the mid-1800s.

Note there are four sets of two poses each. The images are not stereoscopic (like the ones we learned about last class and saw examples of at the No Man's Land exhibit at Rick Wester Fine Art ) they are simply 'Take 1 and Take 2'

Tintypes aka Ferrotypes

The tintype, also known as a ferrotype, is a variation on the Ambrotype, but produced on metallic sheet (not, actually, tin..usually on iron) instead of glass. The plate was coated with collodion and sensitized just before use, as in the wet plate process. It was introduced by Adolphe Alexandre Martin in 1853**, and became instantly popular, particularly in the United States, though it was also widely used by street photographers in Great Britain.

That this process appealed to street photographers was not surprising:

* the process was simple enough to enable one to set up business without much capital.

* It was much faster than other processes of the time: first, the base did not need drying, and secondly, no negative was needed, so it was a one-stage process.

* Cheap to produce

* being more robust than ambrotypes it could be carried about, sent in the post, or mounted in an album.

* The material could easily be cut up and therefore fitted into lockets, brooches, etc.

The most common size was about the same as the carte-de-visite, 2 1/4'' x 3 1/2'', but both larger and smaller ferrotypes were made. The smallest were "Little Gem" tintypes, about the size of a postage-stamp, made simultaneously on a single plate in a camera with 12 or 16 lenses.

Compared with other processes the tintype tones seem uninteresting. They were often made by unskilled photographers, and their quality was very variable. They do have some significance, however, in that they made photography available to working classes, not just to the more well-to-do. Whereas up till then the taking of a portrait had been more of a special "event" from the introduction of tintypes, we see more relaxed, spontaneous poses. Some tintypes that remain are somewhat poignant. The one shown here is of a child who has died. If this seems bizarre, it would seem to have been quite a practice in the last century.

In fact, the original name for Tintype was "Melainotype." It is perhaps worth adding that there was no tin in them. Some have suggested that the name after the tin shears used to separate the images from the whole plate, others that it was just a way of saying "cheap metal" (ie non-silver).

The print would come out laterally reversed (as one sees oneself in a mirror); either people did not worry about this, or just possibly they did not discover it until after the photographer had disappeared!***

Being quite rugged, tintypes could be sent by post, and many astute tintypists did quite a trade in America during the Civil War, visiting the encampments. Later, some even had their shop on river-boats.

Tintypes were eventually superseded by gelatin emulsion dry plates in the 1880s, though street photographers in various parts of the world continued with this process until the 1950s; the writer well remembers being photographed by one of these street photographers in Argentina, when he was a boy. Eventually, of course, 35mm and Polaroid photography were to replace these entirely.

** Professor Hamilton L. Smith was the first to make ferrotypes in the Unites States, and he and Victor Moreau Griswold introduced the process to the photographic industry.

*** Sometimes failure to recognise this has led to false assumptions. (See HERE).

Tintype process video:

John Coffer news video

text from rleggat

That this process appealed to street photographers was not surprising:

* the process was simple enough to enable one to set up business without much capital.

* It was much faster than other processes of the time: first, the base did not need drying, and secondly, no negative was needed, so it was a one-stage process.

* Cheap to produce

* being more robust than ambrotypes it could be carried about, sent in the post, or mounted in an album.

* The material could easily be cut up and therefore fitted into lockets, brooches, etc.

The most common size was about the same as the carte-de-visite, 2 1/4'' x 3 1/2'', but both larger and smaller ferrotypes were made. The smallest were "Little Gem" tintypes, about the size of a postage-stamp, made simultaneously on a single plate in a camera with 12 or 16 lenses.

Compared with other processes the tintype tones seem uninteresting. They were often made by unskilled photographers, and their quality was very variable. They do have some significance, however, in that they made photography available to working classes, not just to the more well-to-do. Whereas up till then the taking of a portrait had been more of a special "event" from the introduction of tintypes, we see more relaxed, spontaneous poses. Some tintypes that remain are somewhat poignant. The one shown here is of a child who has died. If this seems bizarre, it would seem to have been quite a practice in the last century.

In fact, the original name for Tintype was "Melainotype." It is perhaps worth adding that there was no tin in them. Some have suggested that the name after the tin shears used to separate the images from the whole plate, others that it was just a way of saying "cheap metal" (ie non-silver).

The print would come out laterally reversed (as one sees oneself in a mirror); either people did not worry about this, or just possibly they did not discover it until after the photographer had disappeared!***

Being quite rugged, tintypes could be sent by post, and many astute tintypists did quite a trade in America during the Civil War, visiting the encampments. Later, some even had their shop on river-boats.

Tintypes were eventually superseded by gelatin emulsion dry plates in the 1880s, though street photographers in various parts of the world continued with this process until the 1950s; the writer well remembers being photographed by one of these street photographers in Argentina, when he was a boy. Eventually, of course, 35mm and Polaroid photography were to replace these entirely.

** Professor Hamilton L. Smith was the first to make ferrotypes in the Unites States, and he and Victor Moreau Griswold introduced the process to the photographic industry.

*** Sometimes failure to recognise this has led to false assumptions. (See HERE).

Tintype process video:

John Coffer news video

text from rleggat

Ambrotypes

Ambrotype process

If a very thin under-exposed negative (this is when the negative has not been exposed long enough to fully capture a majority of the scene) is placed in front of a dark background, the image appears like a positive. This is because the silver reflects some light whilst the areas with no silver at all will appear black. This is the principle behind the Ambrotype process, the pictures being more correctly known as Collodion positives.

Ambrotypes were made from the 1850s and up to the late eighties, the process having been invented by Frederick Scott Archer in collaboration with Peter Fry, a colleague. Ambrotypes were direct positives, made by under-exposing collodion on glass negative, bleaching it, and then placing a black background - usually black velvet, occasionally varnish - behind it. Though Ambrotypes slightly resemble Daguerreotypes, the method of production was very different, and Ambrotypes were much cheaper.

The Ambrotype process was yet another method of reducing the cost of photography. It became popular for a number of reasons:

* less exposure time was needed

* production was cheaper and quicker, as no printing was required

* as the negative could be mounted the other way, by placing the collodion side on top of the backing material, there was no lateral reversal, as there was in most Daguerreotypes.

* unlike Daguerreotypes, they could be viewed from any angle

Ambrotypes became very popular, particularly in America. The process is also called "Melainotype" in the European continent.

One of you was asking if it is easy to purchase 19th century images made by the older photographic processes:

It seems like Ambrotypes are much cheaper than Daguereotypes on ebay, but I would still think that the best way to get a hold of them is going to rural thrift / antique shop as a lot of the time they are just a fraction of the cost.

text from rleggat

If a very thin under-exposed negative (this is when the negative has not been exposed long enough to fully capture a majority of the scene) is placed in front of a dark background, the image appears like a positive. This is because the silver reflects some light whilst the areas with no silver at all will appear black. This is the principle behind the Ambrotype process, the pictures being more correctly known as Collodion positives.

Ambrotypes were made from the 1850s and up to the late eighties, the process having been invented by Frederick Scott Archer in collaboration with Peter Fry, a colleague. Ambrotypes were direct positives, made by under-exposing collodion on glass negative, bleaching it, and then placing a black background - usually black velvet, occasionally varnish - behind it. Though Ambrotypes slightly resemble Daguerreotypes, the method of production was very different, and Ambrotypes were much cheaper.

The Ambrotype process was yet another method of reducing the cost of photography. It became popular for a number of reasons:

* less exposure time was needed

* production was cheaper and quicker, as no printing was required

* as the negative could be mounted the other way, by placing the collodion side on top of the backing material, there was no lateral reversal, as there was in most Daguerreotypes.

* unlike Daguerreotypes, they could be viewed from any angle

Ambrotypes became very popular, particularly in America. The process is also called "Melainotype" in the European continent.

One of you was asking if it is easy to purchase 19th century images made by the older photographic processes:

It seems like Ambrotypes are much cheaper than Daguereotypes on ebay, but I would still think that the best way to get a hold of them is going to rural thrift / antique shop as a lot of the time they are just a fraction of the cost.

text from rleggat

Collodion aka Wet Plate process

Collodion aka wet plate process

This process was introduced in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer and marks a watershed in photography.

Up till then the two processes in use were the daguerreotype and the calotype. Daguerreotypes were better than calotypes in terms of detail and quality, but could not be reproduced; calotypes were reproducible, but suffered from the fact that any print would also show the imperfections of the paper.

The search began, then, for a process which would combine the best of both processes - the ability to reproduce fine detail and the capacity to make multiple prints. The ideal would have been to coat light sensitive material on to glass, but the chemicals would not adhere without a suitable binder which obviously had to be clear. At first, Albumen (the white of an egg) was used. Then in 1851 Frederick Scott Archer came across collodion.

Collodion was a viscous liquid - guncotton dissolved in ether and alcohol - which had only been invented in 1846, but which quickly found a use during the Crimean war; when it dried it formed a very thin clear film, which was ideal for dressing and protecting wounds. (One can still obtain this today, for painting over a cut). Collodion was just the answer as far as photography was concerned, for it would provide the binding which was so badly needed. Lewis Carroll, himself a photographer who used collodion, described the process in a poem he called "Hiawatha's Photography."

"First a piece of glass he coated

With Collodion, and plunged it

In a bath of Lunar Caustic

Carefully dissolved in water;

There he left it certain minutes.

Secondly my Hiawatha

Made with cunning hand a mixture

Of the acid Pyro-gallic,

And the Glacial Acetic,

And of alcohol and water:

This developed all the picture.

Finally he fixed each picture

With a saturate solution

Of a certain salt of Soda...."

This "soda" was, of course, hypo. Sometimes potassium cyanide was used, the advantage of this being that the solutions could be washed out by rinsing under a tap for a minute or so, whereas hypo would need much more washing time.

The collodion process had several advantages.

* being more sensitive to light than the calotype process, it reduced the exposure times drastically - to as little as two or three seconds. This opened up a new dimension for photographers, who up till then had generally to portray very still scenes or people.

* because a glass base was used, the images were sharper than with a calotype. (Glass being clear and not having any sort of texture like paper does)

* because the process was never patented, photography became far more widely used.

* the price of a paper print was about a tenth of that of a daguerreotype.

There was however one main disadvantage: the process was by no means an easy one. First the collodion had to be spread carefully over the entire plate. The plate then had to be sensitised, exposed and developed whilst the plate was still wet; the sensitivity dropped once the collodion had dried. It is often known as the wet plate collodion process for this reason.

The process was labour-intensive enough in a studio's darkroom, but quite a feat if one wanted to do some photography on location. Some took complete darkroom tents, Fenton (whose is most famous for photographing the Crimean War, we'll look at his work next class) took a caravan, and it is no mere coincidence that many photographs taken in this period happened to be near rivers or streams! Moreover, at this time there were no enlargements, so if one wanted large prints, there was no alternative but to carry very large cameras. (It is such limitations of the process that make the work of people like the Bisson brothers, Fenton, and others so remarkable).

One might also mention the safety factor. The collodion mixture was not only inflammable but highly explosive. It is reported that several photographers demolished their darkrooms and homes, some even losing their lives, as a result of careless handling of the photographic chemicals.

Despite the advantages the collodion process offered, there were still many who stoutly defended the calotype. A writer in the Journal of the Photographic Society (December 1856) wrote:

"for subjects where texture, gradations of tint and distance are required, there is nothing.... to compare with a good picture from calotype or waxed paper negative."

Moreover, the calotype process was less of an ordeal, especially for travel photographers; paper negatives could be prepared at home, exposed on location, and then developed upon one's return. Hence Diamond used the calotype process for some of his travel photographs, though he used collodion for portraiture and for his medical photography.

Nevertheless the invention of this process turned out to be a watershed as far as photography was concerned:

* cheaper alternatives, such as Ambrotypes and Tintypes were developed. The former was a positive on glass, the latter a positive on metal;

* stereoscopic photography began to flourish;

* the carte-de-visite craze started;

* because of the faster speed of the process, the analysis of movement (ex: Eadward Muybridge, whose work we will probably look at during class 4) became possible.

The use of collodion caught on very quickly indeed, and within a few years few people used either the Daguerreotype or Calotype process.

The records of the Photographic Society give an interesting account of the efforts to ensure even sensitivity of the Collodion plates. As mentioned above, these plates had to be dipped into a nitrate of silver bath and exposed whilst still wet. Exposure would have to be almost immediate as otherwise the top of the plate would lose its moisture and the sensitivity would become uneven. All sorts of liquids were tried, including honey, beer, and even rasperry syrup!

text from rleggat

Here is a video we watched in class about the wet plate process:

This process was introduced in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer and marks a watershed in photography.

Up till then the two processes in use were the daguerreotype and the calotype. Daguerreotypes were better than calotypes in terms of detail and quality, but could not be reproduced; calotypes were reproducible, but suffered from the fact that any print would also show the imperfections of the paper.

The search began, then, for a process which would combine the best of both processes - the ability to reproduce fine detail and the capacity to make multiple prints. The ideal would have been to coat light sensitive material on to glass, but the chemicals would not adhere without a suitable binder which obviously had to be clear. At first, Albumen (the white of an egg) was used. Then in 1851 Frederick Scott Archer came across collodion.

Collodion was a viscous liquid - guncotton dissolved in ether and alcohol - which had only been invented in 1846, but which quickly found a use during the Crimean war; when it dried it formed a very thin clear film, which was ideal for dressing and protecting wounds. (One can still obtain this today, for painting over a cut). Collodion was just the answer as far as photography was concerned, for it would provide the binding which was so badly needed. Lewis Carroll, himself a photographer who used collodion, described the process in a poem he called "Hiawatha's Photography."

"First a piece of glass he coated

With Collodion, and plunged it

In a bath of Lunar Caustic

Carefully dissolved in water;

There he left it certain minutes.

Secondly my Hiawatha

Made with cunning hand a mixture

Of the acid Pyro-gallic,

And the Glacial Acetic,

And of alcohol and water:

This developed all the picture.

Finally he fixed each picture

With a saturate solution

Of a certain salt of Soda...."

This "soda" was, of course, hypo. Sometimes potassium cyanide was used, the advantage of this being that the solutions could be washed out by rinsing under a tap for a minute or so, whereas hypo would need much more washing time.

The collodion process had several advantages.

* being more sensitive to light than the calotype process, it reduced the exposure times drastically - to as little as two or three seconds. This opened up a new dimension for photographers, who up till then had generally to portray very still scenes or people.

* because a glass base was used, the images were sharper than with a calotype. (Glass being clear and not having any sort of texture like paper does)

* because the process was never patented, photography became far more widely used.

* the price of a paper print was about a tenth of that of a daguerreotype.

There was however one main disadvantage: the process was by no means an easy one. First the collodion had to be spread carefully over the entire plate. The plate then had to be sensitised, exposed and developed whilst the plate was still wet; the sensitivity dropped once the collodion had dried. It is often known as the wet plate collodion process for this reason.

The process was labour-intensive enough in a studio's darkroom, but quite a feat if one wanted to do some photography on location. Some took complete darkroom tents, Fenton (whose is most famous for photographing the Crimean War, we'll look at his work next class) took a caravan, and it is no mere coincidence that many photographs taken in this period happened to be near rivers or streams! Moreover, at this time there were no enlargements, so if one wanted large prints, there was no alternative but to carry very large cameras. (It is such limitations of the process that make the work of people like the Bisson brothers, Fenton, and others so remarkable).

One might also mention the safety factor. The collodion mixture was not only inflammable but highly explosive. It is reported that several photographers demolished their darkrooms and homes, some even losing their lives, as a result of careless handling of the photographic chemicals.

Despite the advantages the collodion process offered, there were still many who stoutly defended the calotype. A writer in the Journal of the Photographic Society (December 1856) wrote:

"for subjects where texture, gradations of tint and distance are required, there is nothing.... to compare with a good picture from calotype or waxed paper negative."

Moreover, the calotype process was less of an ordeal, especially for travel photographers; paper negatives could be prepared at home, exposed on location, and then developed upon one's return. Hence Diamond used the calotype process for some of his travel photographs, though he used collodion for portraiture and for his medical photography.

Nevertheless the invention of this process turned out to be a watershed as far as photography was concerned:

* cheaper alternatives, such as Ambrotypes and Tintypes were developed. The former was a positive on glass, the latter a positive on metal;

* stereoscopic photography began to flourish;

* the carte-de-visite craze started;

* because of the faster speed of the process, the analysis of movement (ex: Eadward Muybridge, whose work we will probably look at during class 4) became possible.

The use of collodion caught on very quickly indeed, and within a few years few people used either the Daguerreotype or Calotype process.

The records of the Photographic Society give an interesting account of the efforts to ensure even sensitivity of the Collodion plates. As mentioned above, these plates had to be dipped into a nitrate of silver bath and exposed whilst still wet. Exposure would have to be almost immediate as otherwise the top of the plate would lose its moisture and the sensitivity would become uneven. All sorts of liquids were tried, including honey, beer, and even rasperry syrup!

text from rleggat

Here is a video we watched in class about the wet plate process:

Hippolyte Bayard

Hippolyte Bayard

b. 1801, d. 1887

French

Experimenting during his time off from his job as a civil servant, Hippolyte Bayard purportedly invented photography earlier than Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre in France and William Henry Fox Talbot in England, the two men traditionally credited with its invention. Bayard was reportedly persuaded by a friend of Daguerre to postpone the announcement of his findings, thus missing the opportunity to be recognized as the inventor of the medium. In 1840 he responded to this injustice by creating perhaps the first example of political-protest photography, a portrait of himself as a drowned man, upon which he wrote:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government, which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life...! ... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him."

He continues:

"Ladies and gentlemen, you'd better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay."

In fact Bayard did not drown himself but continued to photograph until his death nearly fifty years later. He was the first photographer to be granted a mission héliographique by the Commission des Monuments Historiques to document architecture in France.

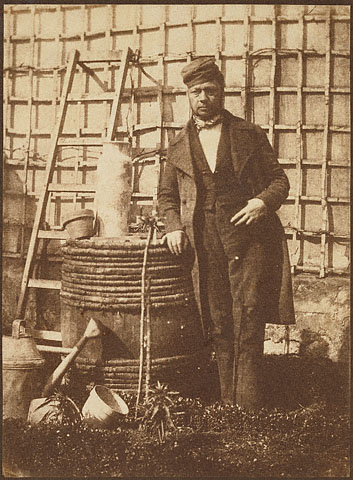

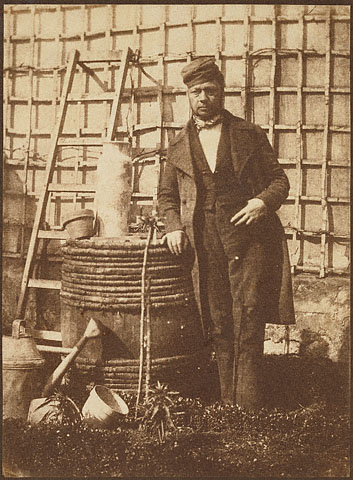

Another self-portrait by Hippolyte Bayard (1847) in the Getty Museum's Collection, this example presents Bayard as a man of the middle class. Although not dressed to plunge his hands in the earth, he looks at home in his garden, surrounded by the commonplace tools of the trade: a barrel, a rustic vase, empty terracotta pots, a watering can, a ladder, and a trellis. The beginning of a vine adorns the trellis and new growth appears at his feet, both of which suggest a new season for the garden as well as the gardener. His confident, proud stance suggests that Bayard was also a gentleman gardener very keen to identify himself with his pastime.

A construction worker stands below eye-level amidst the geometric structure of a two-story building. This photographic view of daily life in the 1840s was quite unusual, demonstrating Hippolyte Bayard's early interest in what later came to be considered a social-documentary approach.

Aside from his human subject, Bayard seemed drawn to the negative shapes of the broken glass pane of a shuttered window and those of the barred one below. These graphical forms support the photograph's gridlike composition, which seems curiously at odds with its gentle framing. The oval mask may have been an attempt to soften the subject's starkness, following a fine-art approach adopted by photographers in the 1800s.

Bayard made many views of Paris in the early years following photography's invention, favoring the British-invented calotype process over France's daguerreotype process. He created this photograph several years before working on a series of architectural studies for the Commission des Monuments Historiques' Mission Héliographique, a French government-sponsored project to record historic buildings around the city. It also predates Eugène Atget's atmospheric, Parisian street scenes made some fifty years later.

This image (1842) is an early example of a scientific fundamental of photography--the light sensitive nature of certain chemical compounds. Without the use of a camera or lens, Hippolyte Bayard carefully arranged a delicate selection of laces and flora on a sheet of paper that was made sensitive to light with a combination of iron salts that produced a blue-toned cyanotype when developed. The sheet of sensitized paper with the objects placed upon it is exposed to sunlight in order to make a camera-less photogenic drawing.

The opacity of the object blocks the light in relation to its density, thus creating a silhouette of the object on the paper. Because the process was relatively uncomplicated, cyanotypes provided a quick method of recording easily recognizable shapes and patterns. Bayard filled the entire sheet of paper, creating a catalog of specimens that reveals the basic structure of each flower, leaf, feather, and scrap of fabric.

Text from Getty

b. 1801, d. 1887

French

Experimenting during his time off from his job as a civil servant, Hippolyte Bayard purportedly invented photography earlier than Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre in France and William Henry Fox Talbot in England, the two men traditionally credited with its invention. Bayard was reportedly persuaded by a friend of Daguerre to postpone the announcement of his findings, thus missing the opportunity to be recognized as the inventor of the medium. In 1840 he responded to this injustice by creating perhaps the first example of political-protest photography, a portrait of himself as a drowned man, upon which he wrote:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government, which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life...! ... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him."

He continues:

"Ladies and gentlemen, you'd better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay."

In fact Bayard did not drown himself but continued to photograph until his death nearly fifty years later. He was the first photographer to be granted a mission héliographique by the Commission des Monuments Historiques to document architecture in France.

Another self-portrait by Hippolyte Bayard (1847) in the Getty Museum's Collection, this example presents Bayard as a man of the middle class. Although not dressed to plunge his hands in the earth, he looks at home in his garden, surrounded by the commonplace tools of the trade: a barrel, a rustic vase, empty terracotta pots, a watering can, a ladder, and a trellis. The beginning of a vine adorns the trellis and new growth appears at his feet, both of which suggest a new season for the garden as well as the gardener. His confident, proud stance suggests that Bayard was also a gentleman gardener very keen to identify himself with his pastime.

A construction worker stands below eye-level amidst the geometric structure of a two-story building. This photographic view of daily life in the 1840s was quite unusual, demonstrating Hippolyte Bayard's early interest in what later came to be considered a social-documentary approach.

Aside from his human subject, Bayard seemed drawn to the negative shapes of the broken glass pane of a shuttered window and those of the barred one below. These graphical forms support the photograph's gridlike composition, which seems curiously at odds with its gentle framing. The oval mask may have been an attempt to soften the subject's starkness, following a fine-art approach adopted by photographers in the 1800s.

Bayard made many views of Paris in the early years following photography's invention, favoring the British-invented calotype process over France's daguerreotype process. He created this photograph several years before working on a series of architectural studies for the Commission des Monuments Historiques' Mission Héliographique, a French government-sponsored project to record historic buildings around the city. It also predates Eugène Atget's atmospheric, Parisian street scenes made some fifty years later.

This image (1842) is an early example of a scientific fundamental of photography--the light sensitive nature of certain chemical compounds. Without the use of a camera or lens, Hippolyte Bayard carefully arranged a delicate selection of laces and flora on a sheet of paper that was made sensitive to light with a combination of iron salts that produced a blue-toned cyanotype when developed. The sheet of sensitized paper with the objects placed upon it is exposed to sunlight in order to make a camera-less photogenic drawing.

The opacity of the object blocks the light in relation to its density, thus creating a silhouette of the object on the paper. Because the process was relatively uncomplicated, cyanotypes provided a quick method of recording easily recognizable shapes and patterns. Bayard filled the entire sheet of paper, creating a catalog of specimens that reveals the basic structure of each flower, leaf, feather, and scrap of fabric.

Text from Getty

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Amy Stein: Stranded

Friday, February 19, 2010

7:30pm - 9:30pm

55 Washington Street, No. 802, Brooklyn, NY

Photographer Amy Stein will discuss her new series Stranded and speak with renowned art critic Lyle Rexer about the themes that run between her images and Kelly Reichardt’s award winning film Wendy and Lucy.

Conversation: Lyle Rexer and Amy Stein

7:30pm - 8:15pm

The conversation will be followed by a special screening of the film. This screening is part of Caption’s current exhibit "Instruments of Empire: Photographs by Amy Stein and Brian Ulrich."

Screening: Wendy and Lucy

8:15pm - 9:30pm

7:30pm - 9:30pm

55 Washington Street, No. 802, Brooklyn, NY

Photographer Amy Stein will discuss her new series Stranded and speak with renowned art critic Lyle Rexer about the themes that run between her images and Kelly Reichardt’s award winning film Wendy and Lucy.

Conversation: Lyle Rexer and Amy Stein

7:30pm - 8:15pm

The conversation will be followed by a special screening of the film. This screening is part of Caption’s current exhibit "Instruments of Empire: Photographs by Amy Stein and Brian Ulrich."

Screening: Wendy and Lucy

8:15pm - 9:30pm

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Assignment #1

Last week we saw Timothy Briner's: Boonville show at Daniel Cooney Fine Art.

Your first assignment is to come up with 3 questions. We are going to be doing a collaborative class interview through email with Timothy that he has very graciously agreed to.

Please take a look at the photographs again and try to come up with detailed questions about the work.

Bring them in to class on Saturday.

Also, please look through the work and press releases of the other three shows we saw: Diane Arbus, William Egglston, Aaron Siskind and be prepared to discuss them in class.

Links to those works are a couple posts down.

Your first assignment is to come up with 3 questions. We are going to be doing a collaborative class interview through email with Timothy that he has very graciously agreed to.

Please take a look at the photographs again and try to come up with detailed questions about the work.

Bring them in to class on Saturday.

Also, please look through the work and press releases of the other three shows we saw: Diane Arbus, William Egglston, Aaron Siskind and be prepared to discuss them in class.

Links to those works are a couple posts down.

Don't Ask Don't Tell.

With the possible overturning of the don't ask don't tell policy of the United States military, I thought this project was both an important part of our country's/photography's history as well as just visually striking.

Please take a look at both the work of Jeff Sheng and his artist statement on the website and think about

a) How much of a person do we need to see for it to be a portrait of them.

b) The relationship of the photographer to the subject in this series.

Please take a look at both the work of Jeff Sheng and his artist statement on the website and think about

a) How much of a person do we need to see for it to be a portrait of them.

b) The relationship of the photographer to the subject in this series.

Monday, February 8, 2010

An invention of the devil brought to you by a French man.

First, the name. We owe the name "Photography" to Sir John Herschel , who first used the term in 1839, the year the photographic process became public. (*1) The word is derived from the Greek words for light and writing.

There are two distinct scientific processes that combine to make photography possible. It is somewhat surprising that photography was not invented earlier than the 1830s, because these processes had been known for quite some time. It was not until the two distinct scientific processes had been put together that photography came into being.

The first of these processes was optical. The Camera Obscura (dark room) which an Arabian scholar Ibn Al-Haythan was credited with first describing c. 1000 ad. and

There is a drawing, dated 1519, of a Camera Obscura by Leonardo da Vinci; about this same period its use as an aid to drawing was being advocated.

The second process was chemical. For hundreds of years before photography was invented, people had been aware, for example, that some colors are bleached in the sun, but they had made little distinction between heat, air and light.

* In the sixteen hundreds Robert Boyle, a founder of the Royal Society, had reported that silver chloride turned dark under exposure, but he appeared to believe that it was caused by exposure to the air, rather than to light.

* Angelo Sala, in the early seventeenth century, noticed that powdered nitrate of silver is blackened by the sun.

* In 1727 Johann Heinrich Schulze discovered that certain liquids change colour when exposed to light.

* At the beginning of the nineteenth century Thomas Wedgwood was conducting experiments; he had successfully captured images, but his silhouettes could not survive, as there was no known method of making the image permanent.

The first successful picture was produced in June/July 1827 by Niépce, using material that hardened on exposure to light. This picture required an exposure of eight hours.

On 4 January 1829 Niépce agreed to go into partnership with Louis Daguerre. Niépce died only four years later, but Daguerre continued to experiment. Soon he had discovered a way of developing photographic plates, a process which greatly reduced the exposure time from eight hours down to half an hour. He also discovered that an image could be made permanent by immersing it in salt.

Following a report on this invention by Paul Delaroche , a leading scholar of the day, the French government bought the rights to it in July 1839. Details of the process were made public on 19 August 1839, and Daguerre named it the Daguerreotype.

The announcement that the Daguerreotype "requires no knowledge of drawing...." and that "anyone may succeed.... and perform as well as the author of the invention" was greeted with enormous interest, and "Daguerreomania" became a craze overnight. An interesting account of these days is given by a writer called Gaudin , who was present the day that the announcement was made.

However, not all people welcomed this exciting invention; some pundits viewed in quite sinister terms. A newspaper report in the Leipzig City Advertiser stated:

"The wish to capture evanescent reflections is not only impossible... but the mere desire alone, the will to do so, is blasphemy. God created man in His own image, and no man- made machine may fix the image of God. Is it possible that God should have abandoned His eternal principles, and allowed a Frenchman... to give to the world an invention of the Devil?"

At that time some artists saw in photography a threat to their livelihood and some even prophesied that painting would cease to exist.

The Daguerreotype process, though good, was expensive, and each picture was a once-only affair. That, to many, would not have been regarded as a disadvantage; it meant that the owner of the portrait could be certain that he had a piece of art that could not be duplicated. If however two copies were required, the only way of coping with this was to use two cameras side by side. There was, therefore, a growing need for a means of copying pictures which daguerreotypes could never satisfy.

Different, and in a sense a rival to the Daguerreotype, was the Calotype (originally called the Talbotype) invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, which was to provide the answer to that problem. His paper to the Royal Society of London, dated 31 January 1839, actually precedes the paper by Daguerre; it was entitled "Some account of the Art of Photogenic drawing, or the process by which natural objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the artist's pencil." He wrote:

"How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably and remain fixed on the paper!"

The earliest paper negative we know of was produced in August 1835; it depicts the now famous window at Lacock Abbey, his home.

The negative is small (1" square), and poor in quality, compared with the striking images produced by the Daguerreotype process.

By 1840, however, Talbot had made some significant improvements, and by 1844 he was able to bring out a photographically illustrated book entitled "The Pencil of nature."

Compared with Daguerreotypes the quality of the early Calotypes was somewhat inferior. However, the great advantage of Talbot's method was that an unlimited number of positive prints could be made. In fact, today's photography is based on the same principle, whereas by comparison the Daguerreotype, for all its quality, was a blind alley.

The mushrooming of photographic establishments reflects photography's growing popularity; from a mere handful in the mid 1840s the number had grown to 66 in 1855, and to 147 two years later. In London, a favourite venue was Regent Street where, in the peak in the mid 'sixties there were no less than forty-two photographic establishments! In America the growth was just as dramatic: in 1850 there were 77 photographic galleries in New York alone. The demand for photographs was such that Charles Baudelaire (1826-1867), a well known poet of the period and a critic of the medium, commented:

"our squalid society has rushed, Narcissus to a man, to gloat at its trivial image on a scrap of metal."

The Daguerreian Society

While mostly Daguerre, Niepce, and Talbot are most known for the invention of photography. There was another man by the name of Hippolyte Bayard who is often not given due credit.

Bayard, a Civil Servant, was one of the earliest of photographers. His invention of photography actually preceded that of Daguerre, for on 24 June 1839 he displayed some thirty of his photographs, and thus at least goes into the record books as being the first person to hold a photographic exhibition. However Francois Arago (a friend of Daguerre and who was seeking to promote his invention) persuaded him to postpone publishing details of his work. When Bayard eventually gave details of the process to the French Academy of Sciences on 24 February 1840, he had lost the opportunity to be regarded as the inventor of photography. As some recompense he was given some money to buy better equipment, but in no way did this atone for the injustice caused him.

More on the importance of Bayard and his list of firsts in class 2.

Most of this text is by Robert Leggat.

There are two distinct scientific processes that combine to make photography possible. It is somewhat surprising that photography was not invented earlier than the 1830s, because these processes had been known for quite some time. It was not until the two distinct scientific processes had been put together that photography came into being.

The first of these processes was optical. The Camera Obscura (dark room) which an Arabian scholar Ibn Al-Haythan was credited with first describing c. 1000 ad. and

There is a drawing, dated 1519, of a Camera Obscura by Leonardo da Vinci; about this same period its use as an aid to drawing was being advocated.

The second process was chemical. For hundreds of years before photography was invented, people had been aware, for example, that some colors are bleached in the sun, but they had made little distinction between heat, air and light.

* In the sixteen hundreds Robert Boyle, a founder of the Royal Society, had reported that silver chloride turned dark under exposure, but he appeared to believe that it was caused by exposure to the air, rather than to light.

* Angelo Sala, in the early seventeenth century, noticed that powdered nitrate of silver is blackened by the sun.

* In 1727 Johann Heinrich Schulze discovered that certain liquids change colour when exposed to light.

* At the beginning of the nineteenth century Thomas Wedgwood was conducting experiments; he had successfully captured images, but his silhouettes could not survive, as there was no known method of making the image permanent.

The first successful picture was produced in June/July 1827 by Niépce, using material that hardened on exposure to light. This picture required an exposure of eight hours.

On 4 January 1829 Niépce agreed to go into partnership with Louis Daguerre. Niépce died only four years later, but Daguerre continued to experiment. Soon he had discovered a way of developing photographic plates, a process which greatly reduced the exposure time from eight hours down to half an hour. He also discovered that an image could be made permanent by immersing it in salt.

Following a report on this invention by Paul Delaroche , a leading scholar of the day, the French government bought the rights to it in July 1839. Details of the process were made public on 19 August 1839, and Daguerre named it the Daguerreotype.

The announcement that the Daguerreotype "requires no knowledge of drawing...." and that "anyone may succeed.... and perform as well as the author of the invention" was greeted with enormous interest, and "Daguerreomania" became a craze overnight. An interesting account of these days is given by a writer called Gaudin , who was present the day that the announcement was made.

However, not all people welcomed this exciting invention; some pundits viewed in quite sinister terms. A newspaper report in the Leipzig City Advertiser stated:

"The wish to capture evanescent reflections is not only impossible... but the mere desire alone, the will to do so, is blasphemy. God created man in His own image, and no man- made machine may fix the image of God. Is it possible that God should have abandoned His eternal principles, and allowed a Frenchman... to give to the world an invention of the Devil?"

At that time some artists saw in photography a threat to their livelihood and some even prophesied that painting would cease to exist.

The Daguerreotype process, though good, was expensive, and each picture was a once-only affair. That, to many, would not have been regarded as a disadvantage; it meant that the owner of the portrait could be certain that he had a piece of art that could not be duplicated. If however two copies were required, the only way of coping with this was to use two cameras side by side. There was, therefore, a growing need for a means of copying pictures which daguerreotypes could never satisfy.

Different, and in a sense a rival to the Daguerreotype, was the Calotype (originally called the Talbotype) invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, which was to provide the answer to that problem. His paper to the Royal Society of London, dated 31 January 1839, actually precedes the paper by Daguerre; it was entitled "Some account of the Art of Photogenic drawing, or the process by which natural objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the artist's pencil." He wrote:

"How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably and remain fixed on the paper!"

The earliest paper negative we know of was produced in August 1835; it depicts the now famous window at Lacock Abbey, his home.

The negative is small (1" square), and poor in quality, compared with the striking images produced by the Daguerreotype process.

By 1840, however, Talbot had made some significant improvements, and by 1844 he was able to bring out a photographically illustrated book entitled "The Pencil of nature."

Compared with Daguerreotypes the quality of the early Calotypes was somewhat inferior. However, the great advantage of Talbot's method was that an unlimited number of positive prints could be made. In fact, today's photography is based on the same principle, whereas by comparison the Daguerreotype, for all its quality, was a blind alley.

The mushrooming of photographic establishments reflects photography's growing popularity; from a mere handful in the mid 1840s the number had grown to 66 in 1855, and to 147 two years later. In London, a favourite venue was Regent Street where, in the peak in the mid 'sixties there were no less than forty-two photographic establishments! In America the growth was just as dramatic: in 1850 there were 77 photographic galleries in New York alone. The demand for photographs was such that Charles Baudelaire (1826-1867), a well known poet of the period and a critic of the medium, commented:

"our squalid society has rushed, Narcissus to a man, to gloat at its trivial image on a scrap of metal."

The Daguerreian Society

While mostly Daguerre, Niepce, and Talbot are most known for the invention of photography. There was another man by the name of Hippolyte Bayard who is often not given due credit.

Bayard, a Civil Servant, was one of the earliest of photographers. His invention of photography actually preceded that of Daguerre, for on 24 June 1839 he displayed some thirty of his photographs, and thus at least goes into the record books as being the first person to hold a photographic exhibition. However Francois Arago (a friend of Daguerre and who was seeking to promote his invention) persuaded him to postpone publishing details of his work. When Bayard eventually gave details of the process to the French Academy of Sciences on 24 February 1840, he had lost the opportunity to be regarded as the inventor of photography. As some recompense he was given some money to buy better equipment, but in no way did this atone for the injustice caused him.

More on the importance of Bayard and his list of firsts in class 2.

Most of this text is by Robert Leggat.

Saturday, February 6, 2010

And so it begins.

Welcome. Please check this a couple times a week as there will be reading assignments / etc.

Here are the shows we are seeing today. So much good stuff all on one street.

Aaron Siskind at Alan Klotz 511 W 25th St 7th fl Klotz Gallery

Timothy Briner at Daniel Cooney. 511 W 25th St #506 Daniel Cooney Fine Art

William Eggleston: 21st Century at Cheim & Reid. 547 W 25th St Cheim & Reid

Diane Arbus: In The Absence of Others. Also at Cheim Reid

My email: MaxTakesPhotos@yahoo.com

Here are the shows we are seeing today. So much good stuff all on one street.

Aaron Siskind at Alan Klotz 511 W 25th St 7th fl Klotz Gallery

Timothy Briner at Daniel Cooney. 511 W 25th St #506 Daniel Cooney Fine Art

William Eggleston: 21st Century at Cheim & Reid. 547 W 25th St Cheim & Reid

Diane Arbus: In The Absence of Others. Also at Cheim Reid

My email: MaxTakesPhotos@yahoo.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)