b. 1801, d. 1887

French

Experimenting during his time off from his job as a civil servant, Hippolyte Bayard purportedly invented photography earlier than Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre in France and William Henry Fox Talbot in England, the two men traditionally credited with its invention. Bayard was reportedly persuaded by a friend of Daguerre to postpone the announcement of his findings, thus missing the opportunity to be recognized as the inventor of the medium. In 1840 he responded to this injustice by creating perhaps the first example of political-protest photography, a portrait of himself as a drowned man, upon which he wrote:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government, which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life...! ... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him."

He continues:

"Ladies and gentlemen, you'd better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay."

In fact Bayard did not drown himself but continued to photograph until his death nearly fifty years later. He was the first photographer to be granted a mission héliographique by the Commission des Monuments Historiques to document architecture in France.

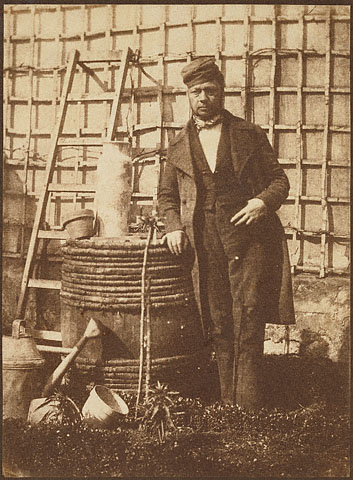

Another self-portrait by Hippolyte Bayard (1847) in the Getty Museum's Collection, this example presents Bayard as a man of the middle class. Although not dressed to plunge his hands in the earth, he looks at home in his garden, surrounded by the commonplace tools of the trade: a barrel, a rustic vase, empty terracotta pots, a watering can, a ladder, and a trellis. The beginning of a vine adorns the trellis and new growth appears at his feet, both of which suggest a new season for the garden as well as the gardener. His confident, proud stance suggests that Bayard was also a gentleman gardener very keen to identify himself with his pastime.

A construction worker stands below eye-level amidst the geometric structure of a two-story building. This photographic view of daily life in the 1840s was quite unusual, demonstrating Hippolyte Bayard's early interest in what later came to be considered a social-documentary approach.

Aside from his human subject, Bayard seemed drawn to the negative shapes of the broken glass pane of a shuttered window and those of the barred one below. These graphical forms support the photograph's gridlike composition, which seems curiously at odds with its gentle framing. The oval mask may have been an attempt to soften the subject's starkness, following a fine-art approach adopted by photographers in the 1800s.

Bayard made many views of Paris in the early years following photography's invention, favoring the British-invented calotype process over France's daguerreotype process. He created this photograph several years before working on a series of architectural studies for the Commission des Monuments Historiques' Mission Héliographique, a French government-sponsored project to record historic buildings around the city. It also predates Eugène Atget's atmospheric, Parisian street scenes made some fifty years later.

This image (1842) is an early example of a scientific fundamental of photography--the light sensitive nature of certain chemical compounds. Without the use of a camera or lens, Hippolyte Bayard carefully arranged a delicate selection of laces and flora on a sheet of paper that was made sensitive to light with a combination of iron salts that produced a blue-toned cyanotype when developed. The sheet of sensitized paper with the objects placed upon it is exposed to sunlight in order to make a camera-less photogenic drawing.

The opacity of the object blocks the light in relation to its density, thus creating a silhouette of the object on the paper. Because the process was relatively uncomplicated, cyanotypes provided a quick method of recording easily recognizable shapes and patterns. Bayard filled the entire sheet of paper, creating a catalog of specimens that reveals the basic structure of each flower, leaf, feather, and scrap of fabric.

Text from Getty

No comments:

Post a Comment