If anyone has an extra $10,000 lying around and some time to kill you can go to this auction today and buy some work from photographers we have talked about in class. If that's a little bit out of your league, you can check the

online gallerySWANN GALLERIES' FEBRUARY 19 AUCTION OF 100 FINE PHOTOGRAPHS FEATURES SCARCE 19th -CENTURY ALBUMS, CLASSIC 20th-CENTURY IMAGES AND CONTEMPORARY ART

On Thursday, February 19, Swann Galleries will conduct an auction of 100 Fine Photographs. The offerings span the entire history of photography, from 19th-century albums through recent works by contemporary artists.

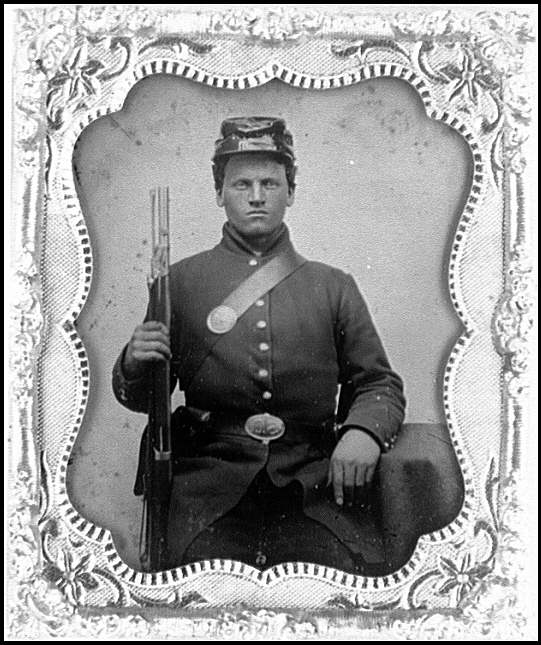

Among the earliest items are rare American daguerreotypes and scarce albums, such as Francis Frith's Egypt and Palestine, Photographed and Described, Vols. I & II, London, 1858-59 (estimate: $6,000 to $9,000); Cités et ruines Américaines, Mitla, Palenque, Izmal, Chichen-Itza, Uxmal, by the French archaeologist Claude-Joseph Désiré Charnay, with 47 albumen photographs of Mexico, including two panoramas, Paris, 1862 (refer to the department for estimate); and a suite of three albums entitled Photographic Pictures Made By Mr. Francis Bedford During the Tour in the East in which, by command, he accompanied His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, with 172 albumen photographs, including views of Egypt, the Holy Land and Syria, and Constantinople and the Mediterranean, London, 1862 ($40,000 to $60,000).

Also from the 19th century are western landscapes by William Henry Jackson, including Shoshone Falls, circa 1883, and The ‘W,' Pike's Peak Carriage Road, circa 1885, mammoth albumen prints ($5,000 to $7,500 each); Edward S. Curtis's studies of Native Americans, as well as A Souvenir of the Harriman Alaska Expedition, May-August 1899, Cook Inlet to Bering Strait and the Return Voyage, Vol. 2, with 107 silver print photographs by Curtis and others, 1899 ($10,000 to $15,000).

There are many appealing images of New York City, including Berenice Abbott's George Washington Bridge II, silver print, 1937, printed 1940s ($5,000 to $7,500), and Flatiron Building, oversize silver print, 1938, printed 1980s ($8,000 to $12,000); Samuel Gottscho's View of New York City, silver print, circa 1930, printed 1940s ($3,000 to $4,500); and Brett Weston's New York (Manhattan Bridge), warm-toned silver print, 1946 ($3,000 to $4,500).

Among Modernist works are André Kertész's Chez Mondrian, silver print, 1926, printed 1960s ($7,000 to $10,000); Henri Cartier-Bresson's Marseilles, silver print, 1932, printed 1980s ($5,000 to $7,500); Margaret Bourke-White's Untitled (Curtiss Gulfhawks), warm-toned silver print, circa 1933 ($8,000 to $12,000); and Manuel Alvarez Bravo's Un Pez que Llaman Sierra [A Fish Called Sword], silver print, 1944, printed 1950s-early 1960s ($10,000 to $15,000).

Among striking portraits are Mike Disfarmer's Mary Jo Seymore, vintage silver print of a G.I.'s gal saluting the camera, circa 1944 ($7,000 to $10,000); Philippe Halsman's Albert Einstein, silver print, 1947, printed 1970s ($5,000 to $7,500); Horst P. Horst's Jacqueline Bouvier [Kennedy], silver print, 1953, the year she married J.F.K.; and Lawrence Schiller's Marilyn Monroe, oversize silver print, 1962, printed 1990s (each $7,000 to $10,000).

Other mid-century highlights include vintage silver prints of Dave Heath's Vengeful Sister, Chicago, 1956 ($6,000 to $9,000); Harry Callahan's Weed, Ai-en-Provence, 1958 ($7,000 to $10,000); and Minor White's Moon & Wall Encrustations, Pultneyville, New York, 1964 ($10,000 to $15,000).

An assortment of desirable contemporary artworks features Joel-Peter Witkin's Canova's Venus, N.Y.C., silver print, 1982; Tina Barney's Beverly, Jill and Polly, color coupler print, 1982 ($7,000 to $10,000 each); and Kara Walker's Testimony, portfolio with five photogravure images of her silhouettes and projections, 2005 ($10,000 to $15,000).

The auction will begin at 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, February 19.

An illustrated catalogue, with information on bidding by mail or fax, is available for $35 from Swann Galleries, Inc., 104 East 25th Street, New York, NY 10010, or online at www.swanngalleries.com.

For further information, and to make advance arrangements to bid by telephone during the auction, please contact Daile Kaplan at (212) 254-4710, extension 21, or via e-mail at dkaplan@swanngalleries.com.