Talbot came across a discovery of using gallic acid to treat photographs much later than Daguerre (which is another reason why his process wasn't as popular at first) and by the fall of 1840, exposure times could be cut down from the expected half hour to 30 seconds on a very bright day.

in 1847 people started using glass negatives coated with albumen (egg whites) to help with the definition and fading problems that were plaguing paper photography, but while the glass negatives had no grain, the procedure was complicated and the exposure time was longer than what was needed for daguerreotypes.

In 1850 Fredrick Scott Archer, an English engraver turned sculptor, published a method of sensitizing a newly discovered colorless and grainless substance, collodion, to be used on glass. Because the exposure was a lot shorter when the plate was used in a moist state (20 times shorter compared to previous methods), the process became known as the wet plate or wet collodion method. An immediate drawback to this process was having to carry a mini darkroom with you to sensitize and then develop every plate you wanted to expose, but the crisp definition and contrast were exactly what many photographers were looking for that paper negatives couldn't offer and the collodion method went on to really expand photographic activity in virtually every genre of the medium.

Unlike Talbot, who tried to say that the collodion method was already covered by one of his calotype patents, Archer looked at his discovery as a gift to the world and did not look to make any money from it (he died impoverished in 1857, only 7 years after his discovery.)

example of a print from wet plate collodion

1854: James Ambrose Cutting invents the ambrotype, a on glass using the wet plate collodion process. The main difference is that the image appears positive and you don't have to make a print from it. Exposures were also made while the plate was still wet with collodion and then dipped in silver nitrate. Exposure ranged from roughly 5 - 60 seconds depending on light conditions. The plate is then developed and fixed. The resulting negative, when viewed by reflected light against a black background, appears to be a positive image: the clear areas look black, and the exposed, opaque areas appear light. (while being a totally different process and final result, the whole aspect of a negative appearing as a positive isn't too far off from daguerreotypes)

ambrotype

Also in 1854: André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri introduces a style of photography using albumen paper. It came to be called the carte-de-visite because the size of the mounted albumen print (4 by 2.5 inches [10.2 by 6 cm]) corresponded to that of a calling card. Disderi used a camera with 4 lenses to produce 8 negatives on a single glass plate. This sped up the whole process by only needing to work with 1 plate to produce up to 8 images that would later be separated. Albumen paper was also used to print from single glass negatives.

carte-de-viste

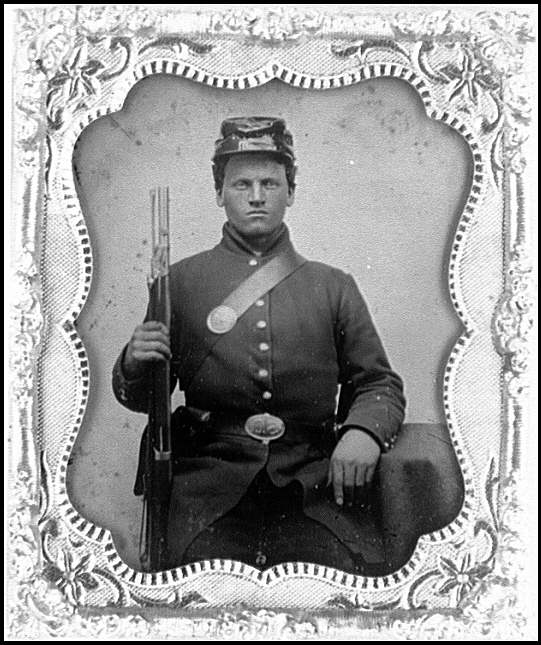

Throughout the 1850s, the ambrotype was becoming more and more popular, weeding out the daguerreotype's popularity, but as the 1860's came along, the tintype started doing just the same to the ambrotype. The tintype (also known as melainotype or ferrotype) was first described in France by Adolphe-Alexandre Martin in 1853 but later patented in the US by Hamilton Smith and by William Kloen of Great Britain both in 1856. The tintype was much like the ambrotype except instead of using glass, there was a black enameled iron and the emulsion was gelatin silver based. Another advantage of the tintype was that they were able to be processed and developed much quicker than previous methods, making them much more practical from a business and customer standpoint.

tintype

- - -

Nadar used direct lighting on his subjects to bring out the features he would normally be accentuating for his caricature work. He used his portraits to assist with his first “PanthéonNadar,” (1854) a set of two gigantic lithographs portraying caricatures of prominent Parisians. Nadar also went on to pioneer aerial photography which was an important advance in map making. He took his first aerial photograph from a hot air balloon in 1858.

Portrait of our favorite critic and photography hater Baudelaire. Late 1850s.

Daumier's satirical lithograph of Nadar elevating the heights of photography.

- - -

In the 1840s, a time when most photographers preferred the clarity of a daguerreotype, David Octavius Hill (Scottish) was using the calotype process to look at composition and overall character instead of specific detail

- - -

Roger Fenton was most likely the first war photographer.

Roger Fenton self portrait.

Along with his assistant Marcus Sparling, their documentation of the Crimean War predated the American Civil War by about 7 years. Fenton had set up their dark room in a wagon and took about 360 photos using the wet plate collodion process. Instead of showing a lot of the action of war, Fenton concentrated more on the mundane. Due to his involvement with the government he chose to show only the “acceptable” parts of the conflict, even his account of the Charge of the Light Brigade (also a poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson) was put in a heroic and glorious account.

Fenton was able to return to London and actually exhibit some of his work. The more noted photographs were turned into wood engravings and printed in the Illustrated London News. After the war, Fenton kept up with architectural and landscape photography until his retirement from the field in 1862 when he decided to to return to practicing law.

Dr. Robert Leggat article about war photography.

Mathew Brady thought it would be a good idea to photograph the entire American Civil War and was sure the American government would later purchase his photos and he would at least make back the $100,000 or so he had invested in the project. While Brady hired roughly 20 photographers such as Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan to work under him, part of the deal was that they could not attain any personal credit for their work and everything shot by them was to be signed as Mathew Brady. This of course did not suit some of the photographers and they went on to branch off and do their own work without the supervision of Brady, who actually didn't even shoot the actual war that much but was more in charge of the supervisions and organization of the project. The war had come to an end in 1865 and by 1873 Brady was far in debt, having to sell off his New York studio. He did, however, manage to finally get the gvt. to buy his project for a whopping $2840...for those of you with minimal math skills that's a loss of $97,160.

Mathew Brady, General Ulysses S. Grant, Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864.

Many of the photographers hired by Brady, such as Gardner were unhappy with not being able to take credit for their work and went on to quit. Gardner had opened up his own studio in D.C. and kept working on the Civil War project without the assistance of Brady and actually had the Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, a two-volume collection of 100 original prints, published in 1866.

When Daguerre exclaimed that photography was "an absolute truth, infinitely more accurate than any painting by the human hand," he probably wasn't thinking of how photographers would be using this public perception to not only push their agenda but just as simply fool the public. While the war photographers of the time were not necessarily trying to do either, the facts are simple: photographing action in the 1860s was really hard, photos were staged, war scenes were tampered with for the sake of better photos. Is this acceptable? Does the photographer have a right to do such a thing? Does it matter if the photograph is an absolute truth if it serves a greater purpose like changing people's perception of the world for a greater truth or is that too close to propaganda?

The Library of Congress has some great information about photographing the Civil War if you want to keep looking at that subject matter.

Abraham Lincoln photo from 1862 by Alexander Gardner

Timothy O'Sullivan started out working with Brady and decided to branch off so he could document the Western American landscape. From 1867 to 1869, he was official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel where his job was to photograph the West to attract settlers.

- - -

William Henry Jackson, another American photographer of the West whose pictures helped convince the Congress to establish National Parks, Like Yellowstone.

- - -

Felice Beato was the 1st photographer to devote himself entirely to photographing in Asia and the Near East. His work ranged from portrait to war photography, and it is believed that he was the first photographer to show human corpses on a battlefield.

- - -

John Thomson (Scottish) followed Beato's lead and headed to the Far East for his documenting purposes. Upon returning to Europe, his work documenting the street people of London helped define social documentary photojournalism. (We'll talk about this in Class 3)

- - -

Gustave Le Gray was a French photographer pioneering the way we now look at subject and technical matter within the medium. While he often worked with traditional landscapes, he brought new techniques of combining multiple exposure to make one print, and was not afraid to turn his camera towards a subject that was generally considered not worthy of a photograph, like a factory building.

- - -

Henry Peach Robinson (English) much like Le Gray often used multiple negatives to make one print, but in his case it was mostly for fictionalized serials like the one above.

No comments:

Post a Comment